Britain's enchanting visitor: The red admiral butterfly

3 Minute Read

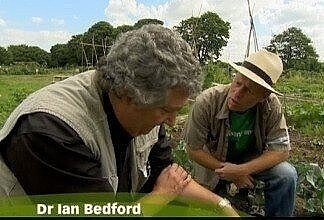

Dr Ian Bedford tells us everything we need to know about the 'bug of the month' for December, the red admiral.What is a red admiral?

Throughout autumn and early winter, it’s very likely that we’ll still be able to see a butterfly in the garden, particularly when the sun is out.

This will invariably be the red admiral, Vanessa atalanta, a distinctive dark-coloured butterfly displaying a broad red stripe on each wing, and white spots at the tip of each forewing.

Although the red admiral is one of Britain’s most seen butterflies throughout most of the year, it would be wrong to assume that it’s a native resident species in this country. Each year large numbers of red admirals migrate to Britain from the warmer parts of Europe and North Africa, arriving here throughout late spring and summer.

The red admiral appears in significant numbers each year and survives well within a wide range of different habitats, unlike many of Britain’s native butterfly species, which nowadays are declining at an alarming rate.

The red admiral appears in significant numbers each year and survives well within a wide range of different habitats, unlike many of Britain’s native butterfly species, which nowadays are declining at an alarming rate.

How does the red admiral thrive in Britain while native butterflies struggle?

The red admiral possesses several behavioural characteristics that enhances its survival capabilities. Primarily, red admirals are robust, fast flying butterflies that are less likely to be caught by predators than other butterflies.

red admirals also lay their eggs singly on the leaves of urtica dioica, the common stinging nettle, whose hollow spines contain a cocktail of chemicals that cause discomfort and pain to deter larger herbivores from eating it.

When the red admiral’s caterpillars hatch, they each intuitively create a protective tent to live, feed, and grow within by fastening the edges of a leaf together with silk. After 3 to 4 weeks, when fully grown, the caterpillars will bind several leaves together to form a chamber, within which they undertake their final skin shed and become a chrysalis. From mid-summer onwards, these chrysalises then hatch into the next generation of adult red admiral butterflies.

These newly emerged butterflies won’t be ready to mate until the following spring, so they spend their days feeding on nectar-rich flowers such as buddleia, or on the fermentation juices of over-ripe summer fruits.

In late autumn, red admirals will often be seen in large numbers on ivy flowers alongside wasps and bees that will be busily stocking up on nectar and pollen for their period of winter hibernation. However, the red admiral butterflies will not fully hibernate, but will either become dormant for a short period of time or succumb to long periods of sub-zero temperatures and die.

As climates change and the planet becomes hotter, Britain’s winters are becoming more frequently mild. So nowadays, it’ll be more common to see a red admiral butterfly on the wing during winter, and for it possibly to survive into spring when the migrants from Europe arrive again.

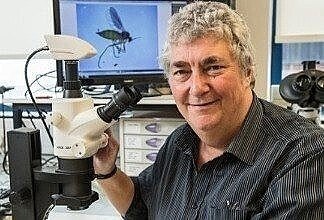

About Dr Ian Bedford

Ian has been fascinated by the bug world for as long as he can remember. From studying butterflies on the South Downs as a youngster, he went on to pursue a career in Research Entomology and ran the Entomology Dept at the John Innes Centre in Norwich up until his recent retirement.VISIT WEBSITE

'Bug of the month'

Visit our 'bug of the month' archive.Every month Ian will shares his knowledge on how to protect your plants and gardens from preventable pest invasions while providing valuable insights into the insects regularly found in our gardens.

find out more

Comments (0)

Why not be the first to send us your thoughts?